Abdul Mannan: Rethinking Myeloid Precursor Disease in 2025

Abdul Mannan, Consultant Haematologist at Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, posted on LinkedIn:

”From Observation to Interception: Rethinking Myeloid Precursor Disease in 2025

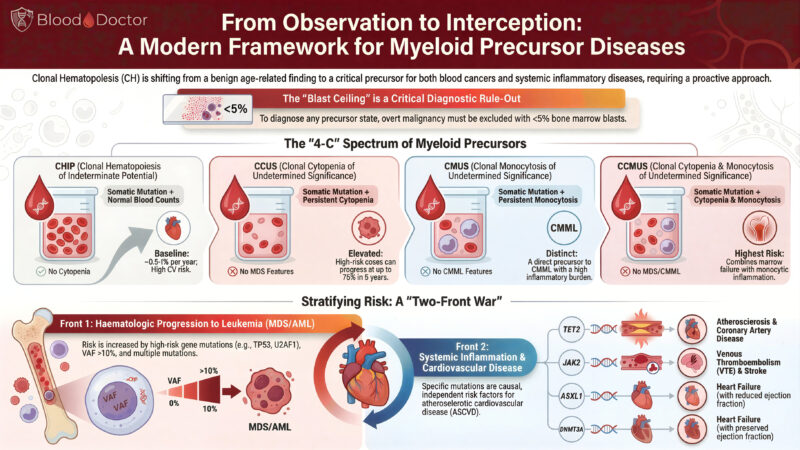

Over the past few years, clonal haematopoiesis has moved from being a “benign curiosity of ageing” to a genuinely important clinical entity. The more we study it, the clearer it becomes that these precursor states don’t just sit quietly in the background. They shape two major fronts of disease: progression to MDS/AML and cardiovascular inflammation.

I’ve put together this infographic to make sense of the evolving landscape and the “4-C” spectrum we now recognise: CHIP, CCUS, CMUS, and CCMUS.

Why this matters

We’re no longer just observing clones; we’re learning when they behave, when they misbehave, and when they need closer follow-up. The old focus on blasts and cytopenias alone doesn’t cut it anymore. There’s a whole inflammatory story unfolding underneath.

Key points from the graphic

CHIP

Somatic mutation, normal counts, no cytopenia. Often found incidentally. Low annual progression risk, but a surprisingly strong link to cardiovascular disease. The heart always wants a cameo role.

CCUS

Somatic mutation plus persistent cytopenia. No MDS-defining features, but some cases progress rapidly. Think of this as CHIP that has decided to cause trouble.

CMUS

Somatic mutation plus persistent monocytosis. This sits on the path towards CMML and carries a high inflammatory burden. A reminder that monocytes are never shy when inflammation is involved.

CCMUS

Cytopenia + monocytosis + mutation. Highest overall risk. The “all-in-one” precursor deserves careful attention.

A Two-Front Battle

The infographic highlights what we’re all seeing in clinics and literature:

1. Front 1: Haematological progression

High-risk mutations (TP53, U2AF1, splicing genes) and VAF >10% increase the likelihood of evolving into MDS/AML.

2. Front 2: Systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease

Mutations in TET2, JAK2, ASXL1, DNMT3A are themselves independent risk factors for:

• coronary artery disease

• venous thrombosis and stroke

• heart failure (both reduced and preserved EF)

It’s not often that haematology, cardiology, and immunology all fight for space on the same slide.

Where this takes us

We’re shifting from passive observation to interception. Early identification, structured follow-up, mutation-informed risk stratification, and collaboration across specialties will define the next decade of care.

If you’re teaching trainees, designing services, or thinking about where haematology is heading, this framework gives a clean, practical way to have those conversations.

Happy to share the high-resolution version, teaching notes, or a breakdown for your MDT or journal club.

Keep moving – one clone at a time.”

Stay updated with Hemostasis Today.

-

Mar 11, 2026, 23:05Ney Carter Borges: A Safety Advantage of Apixaban over Rivaroxaban Without Clear Superiority

-

Mar 11, 2026, 22:01The Results of Landmark COBRRA Trial in Acute VTE Management – ISTH

-

Mar 11, 2026, 21:19Peter Antevy: EMS Rarely Suspects Pediatric Stroke And It’s Costing Kids Time

-

Mar 11, 2026, 19:24Robert Sidonio: Prophylaxis with Wilate and The WIL-31 Study Results

-

Mar 11, 2026, 18:42Annette Logan-Parker: A Hemophilia B Breakthrough – From Weekly Infusions to One Treatment

-

Mar 11, 2026, 18:27Cesar Garrido and Lackram Bodoe Are Advancing WFH Partnerships in Trinidad and Tobago

-

Mar 11, 2026, 18:14Aloke Finn: Silent Plaque Rupture and Healing in Coronary Artery Disease

-

Mar 11, 2026, 17:23Mattia Galli: A Privilege to Collaborate on Such a Complex Topic as Cardio-Rheumatology

-

Mar 11, 2026, 17:12Shubham Misra: Proteomic Biomarkers for Acute Stroke Subtype Classification