What Happens When Collagen Breaks Down? Understanding Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome

Kabilan K. L., Pediatric Cardiac Nurse at Towards Building Health, shared on LinkedIn.

”𝙒𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙞𝙨 𝙀𝙝𝙡𝙚𝙧𝙨-𝘿𝙖𝙣𝙡𝙤𝙨 𝙎𝙮𝙣𝙙𝙧𝙤𝙢𝙚 ?

EDS is a group of inherited (genetic) disorders that affect the body’s connective tissues — in particular collagen and other supporting structures.

Connective tissue is like the body’s “glue” and “scaffolding” — it supports skin, joints, blood vessels, organs, and more.

Because the connective tissue is weaker or abnormal, people with EDS have characteristic features such as loose or overly flexible joints, stretchy skin, fragile tissue, and in some forms, serious vascular or organ-risks.

How it Works (Pathophysiology and Genetics)

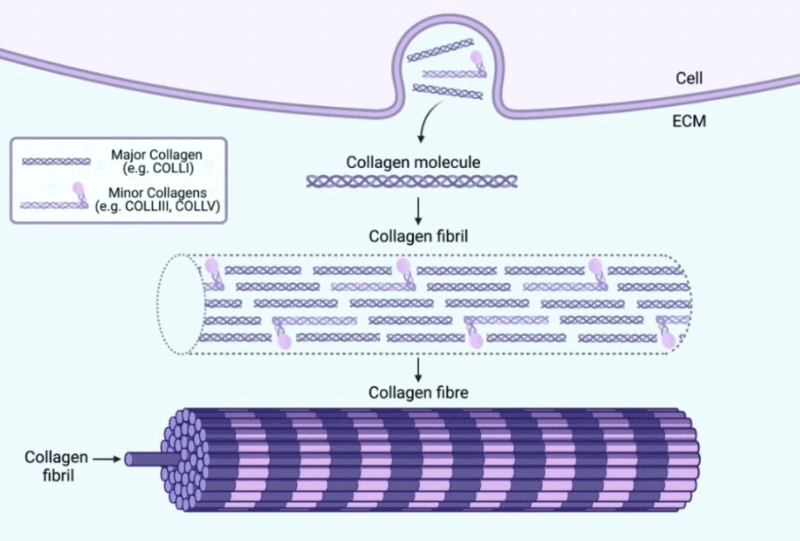

Many forms of EDS are caused by mutations in genes that code for collagen or enzymes, processes that build, shape or cross-link collagen.

When collagen is defective, the connective tissue ends up being weaker, more stretchy, less supportive. For example, blood vessel walls may be thinner or less resilient; skin may stretch more and bruise easily; ligaments may allow joints to move beyond normal limits.

There are 13 major subtypes of EDS recognized (as of recent classification) — each with somewhat different gene defects and clinical features.

Common Signs and Symptoms.

Typical features to look for:

Joint hypermobility: Joints that move beyond the usual range, frequent sprains, dislocations, sub-luxations.

Skin differences: Skin may be very stretchy (hyperextensible), unusually soft or velvety, bruise easily, heal poorly or with abnormal scars.

Vascular, organ risk (in certain subtypes): Fragile blood vessels, risk of arterial rupture or organ rupture (especially in the vascular subtype).

Other symptoms may include chronic pain (especially joint and muscle pain), fatigue, early-onset osteoarthritis, scoliosis or spinal issues, gastrointestinal problems, among others.

Because connective tissue is everywhere, the effects can show up in many organ systems — not just skin and joints.

Types and Classification

There are multiple forms of EDS — here are three fairly common ones:

Classical EDS: Features often include skin hyperextensibility, abnormal scarring, joint hypermobility.

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS): The most common subtype; primarily joint hypermobility, less obvious skin involvement; gene cause not fully established.

Vascular EDS (vEDS): One of the more serious forms, with risk of life-threatening blood vessel or organ rupture.

Diagnosis and Monitoring

Diagnosis usually involves clinical evaluation (looking for joint hypermobility, skin signs, family history) and possibly genetic testing depending on subtype.

For joint hypermobility evaluation, tools like the Beighton score may be used.

In some subtypes, monitoring of cardiovascular system (e.g., aorta, arteries) is important because of rupture risk.

Because EDS is variable, diagnosis may be delayed or missed. Awareness is key.

Treatment and Management

There is no cure for EDS (as of now) — management is supportive.

Stay Consistent.”

Stay updated with Hemostasis Today.

-

Feb 23, 2026, 11:37Charles Okyere Boadu: Blood Donation Helps Lower Your Risk of Stroke and Organ Damage

-

Feb 23, 2026, 11:29Emma Lefrancais: Uncovering A Key Role for The IL-33/ST2 Axis in Platelet Biology with Lucie Gelon

-

Feb 22, 2026, 14:16Ilenia Calcaterra: From Representation to Intellectual Independence in Women in Science

-

Feb 22, 2026, 13:27Pete Stibbs: New AHA and ACC PE Guidelines Finally Align with Real Clinical Practice

-

Feb 22, 2026, 10:39Tagreed Alkaltham: Fibrinogen Concentrate Is a Deliberate Clinical Choice in Acute Bleeding

-

Feb 22, 2026, 09:38Abdulrahman Nasiri: Significant Shifts In The 2026 AHA/ACC Guidelines for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

-

Feb 22, 2026, 09:22Shiny K. Kajal: Not All Transfusion Reactions Are Immunohematologic Incompatibilities

-

Feb 22, 2026, 09:12Arun V J։ The Hidden Risks in Every Blood Bag

-

Feb 22, 2026, 08:56Parandzem Khachatryan։ How Hard Is It to Be a Mom, a Wife, a Professor, and a Doctor All at Once?